My Dad’s WWII Story

CONFESSIONS OF AN AMG OFFICER

FOREWORD

If the U.S. Army had placed you, gentle reader, in charge of a beautiful and trusting war victim, what would you have done?

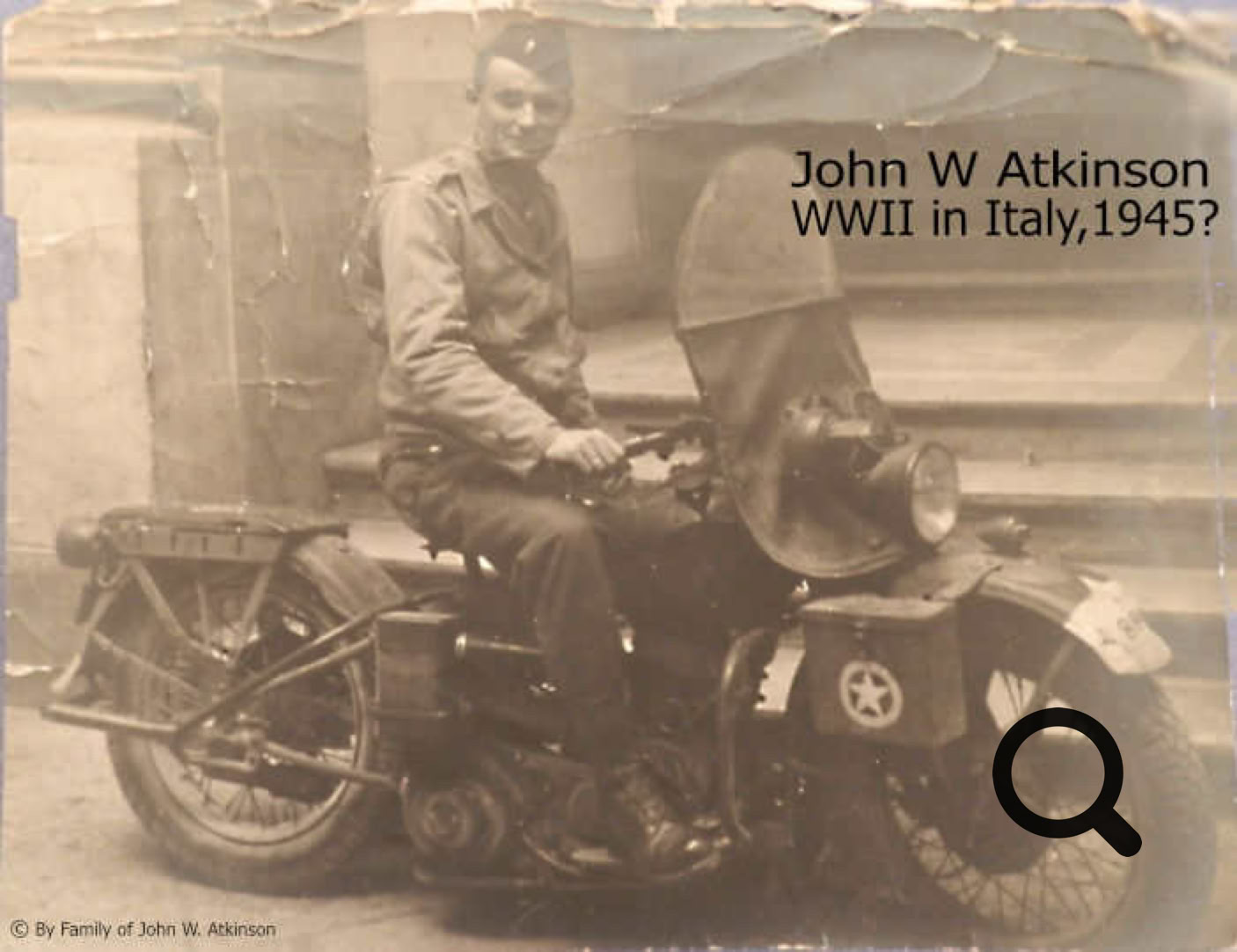

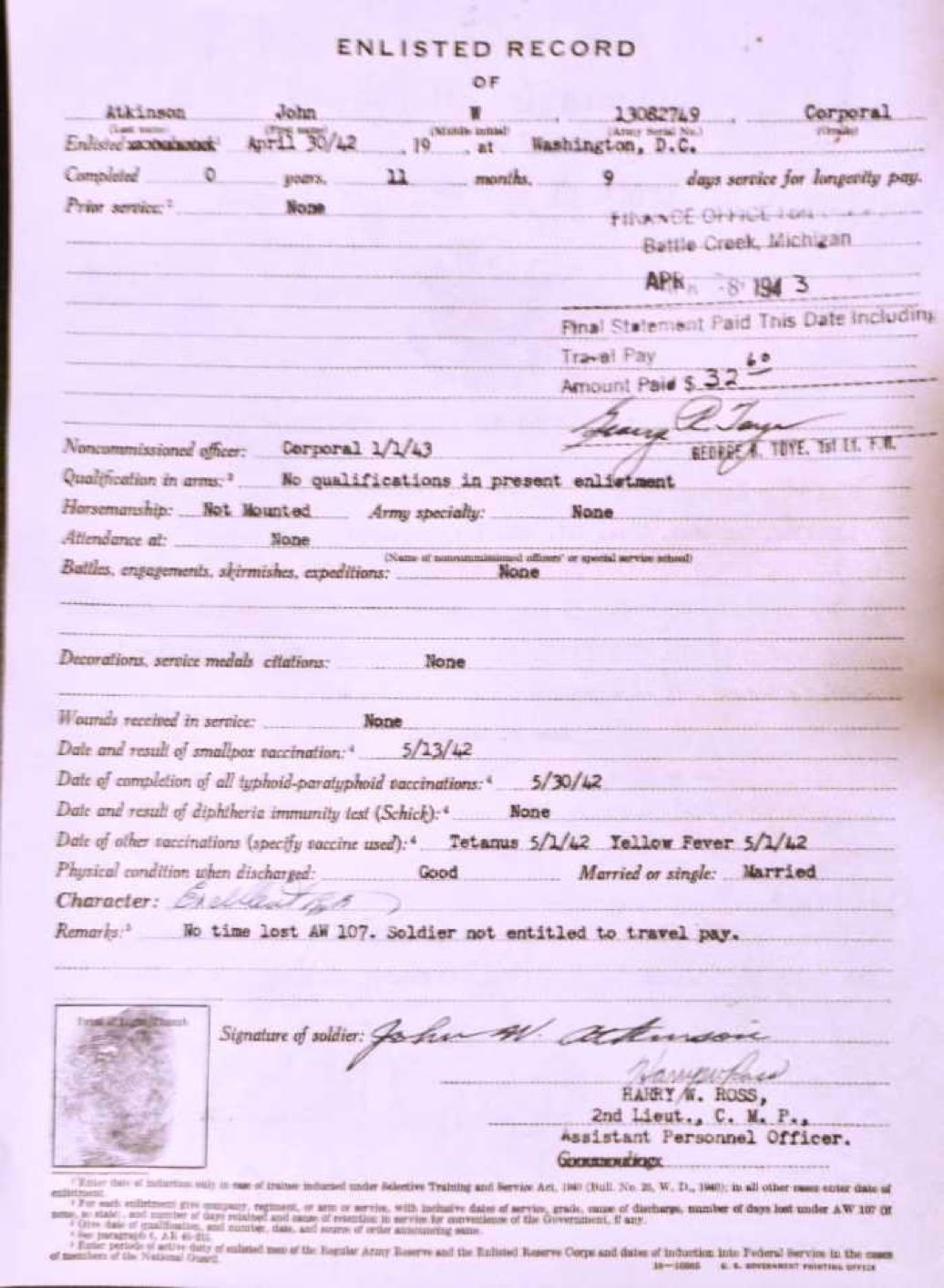

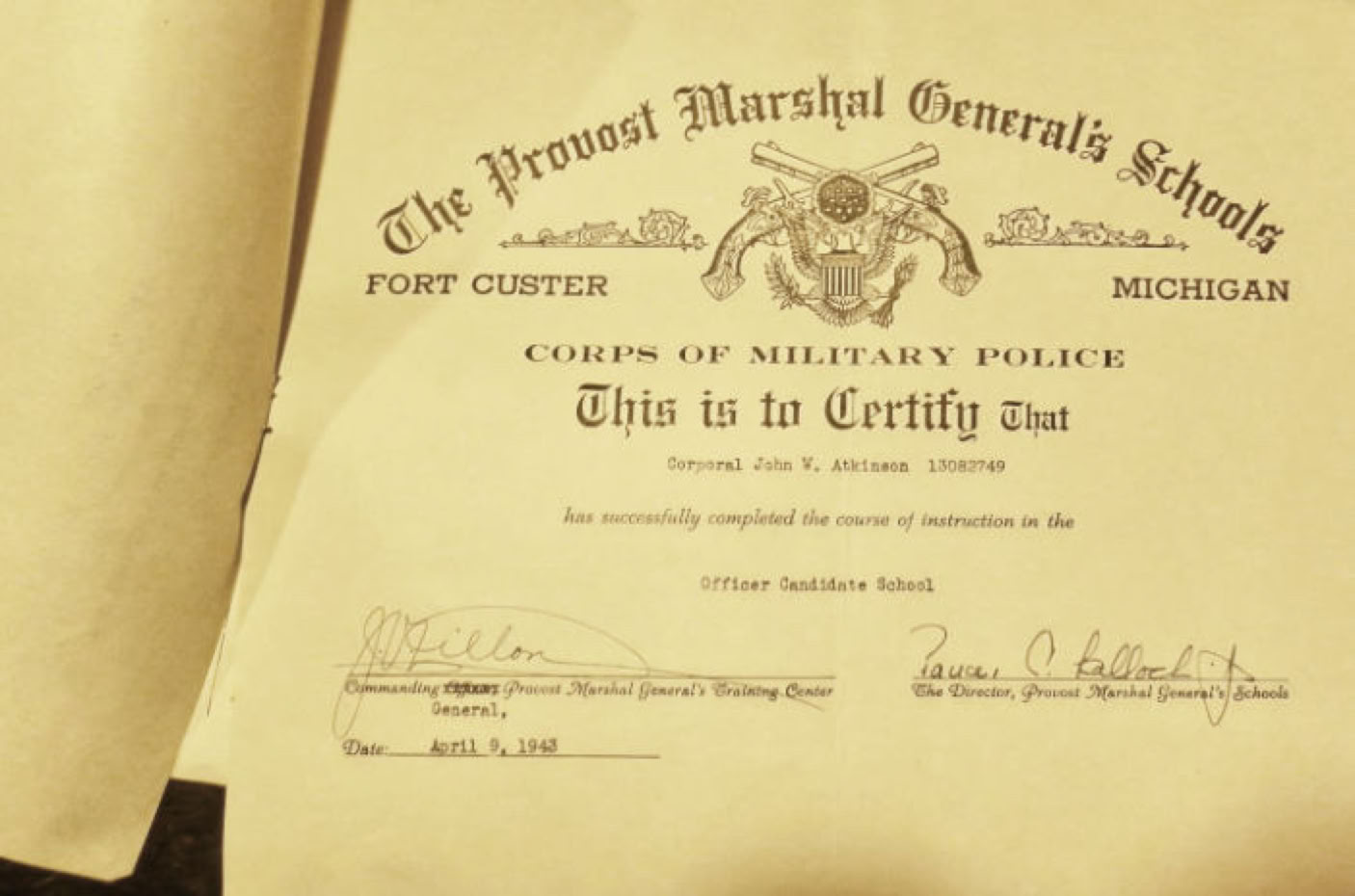

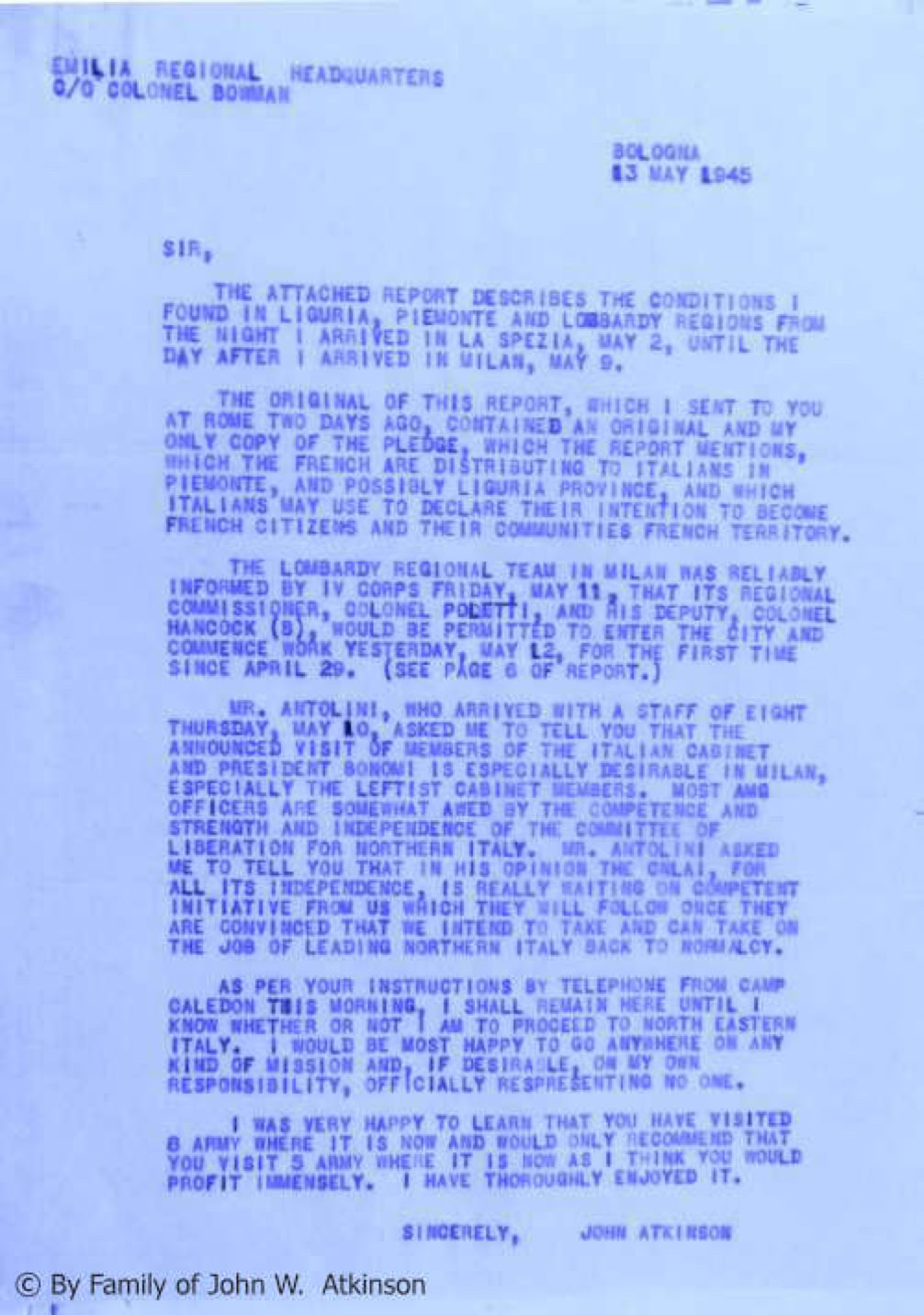

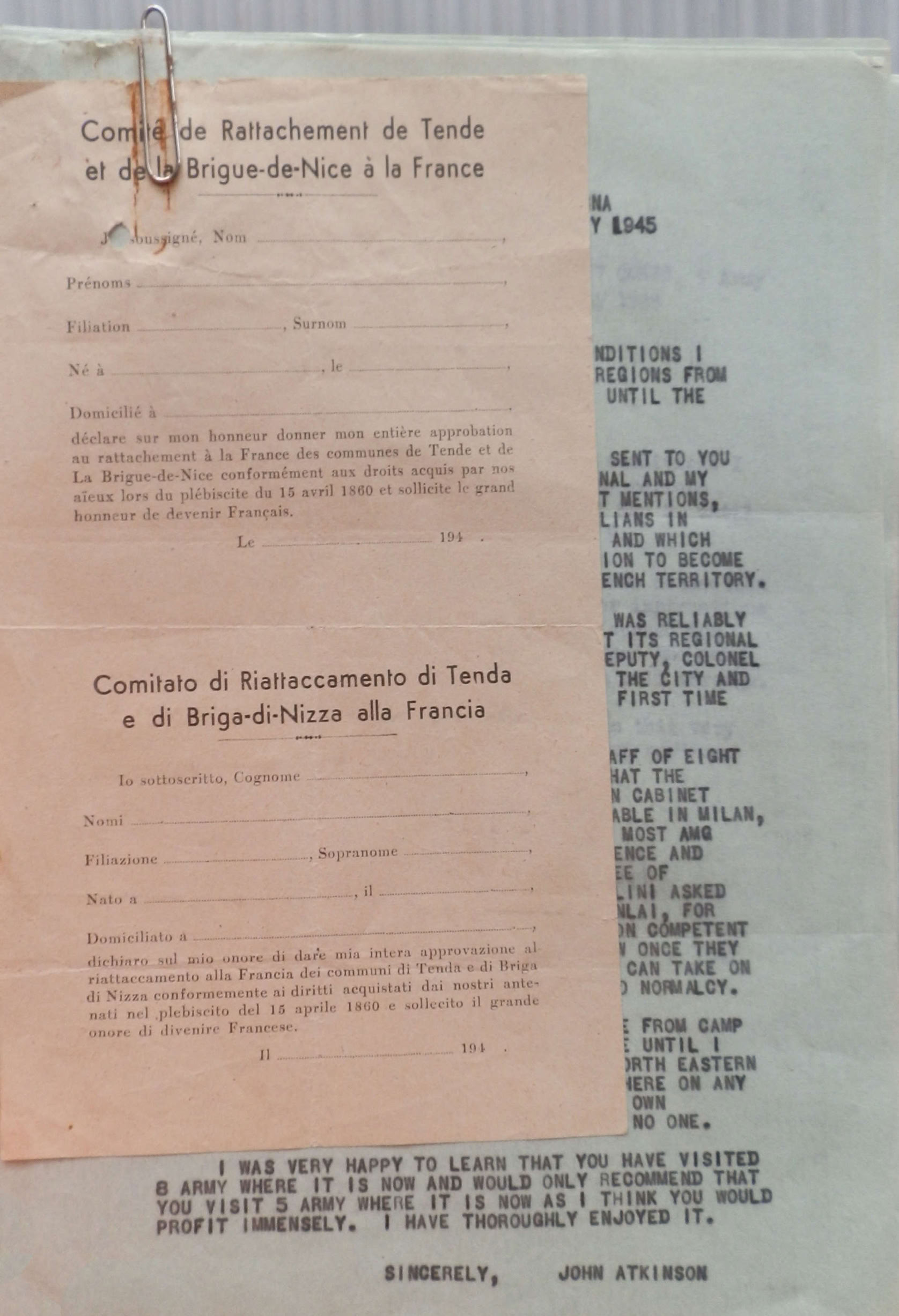

In the spring of 1943 I was plucked out of the military government school for junior officers at Fort Custer, Michigan, and plunked down behind the two allied armies which were then beginning the hard, two-year-long advance up the lovely body of Italy from Sicily to the Alps. I thought my mission included helping the fallen nation back to a better way of life. This was my first mistake.

In this book I have recorded some other mistakes, but some are not my own, and they were deliberate. Even so, it is better to charge our broken trust to youth and ignorance. Then hope is left.

John Atkinson

Arlington, Va.

CONFESSIONS OF AN AMG OFFICER

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

I

Joe liked the girls in their summer dresses. And no wonder. The moving picture extras from suburban Cinema City and the sophisticated career girls from the shops and government offices didn't just stand there. "Ciao bello," they said.

Thus addressed, Good Looking turned tiredly under his infantry pack and grinned through his beard. It was good fun and more like home than the Americans had known in a long time. As a matter of fact he liked it so much that later he took the matter up with the editor of the Mediterranean edition of The Stars & Stripes. "The Joes who are fighting this war should get more leaves to visit the historic monuments," he wrote, omitting all reference to the fact that on June 5, 1944, most Joes had marched around one side of the Coliseum and smack through the center of the forums and market places of ancient Rome.

So quickly had the American Fifth Army swept over the last German delaying actions, down the gradual slopes of the Alban Hills and across the intervening Tiber plain that the main elements of the 34th and 45th divisions were foots logging single file along the New Appian Way toward St. John's Gateway and the inner city before the cry went up: "Here come the Americans!" Drowsing in the moist, early morning heat at the bottom of the ancient river valley, the tired European capital suddenly woke up.

In every grey stone apartment and pastel colored tenement along the line of march, heavy wooden shutters banged open, revealing the whole family just out of bed and wide-eyed with joy. Moments later great iron latch bars clanged loudly in the corridors and inside patios, massive street doors swung inward and civilians of all ages surged out to greet the Joes, Jims, Johns, and Georges who now in their ninth month on the mainland had come to be known to Italians on both sides of the fighting front as simply "JOH."

"Hallo, Joh," a tumult of voices cried. "Take some wine."

Joe smiled quizzically through his sweat and dirt. For nine weary months he'd been fighting practically every yard of the hard, long two hundred eighty miles from Salerno and this was the first town you didn't enter by walking around the remains of buildings piled or scattered about the streets. The well-wishers were well dressed, too, and didn't have the haunting hungry look that was in the eyes of the threadbare people in the ruined towns further south. But the children still scrambled for the paper-wrapped squares of hard candy and the men gladly accepted cigarettes. This was the same. Sugar and tobacco were scarce everywhere.

The main troop movement through town was northward along the Corso Umberto, jammed to the store windows with civilians except for narrow lanes along each curb where Joe walked single file through a never-ending gantlet of welcome. As he approached, more flowers and straw covered flasks full of the good white wine from nearby Frascati were thrust in his face. As he walked away, Italians made interesting remarks about this new kind of soldier from far America.

"Their shoes have rubber heels," they whispered incredulously, as though the fact were something beyond belief. After being informed by their press that America was immobilized because Japan had captured all of her sources of rubber it came as something of a shock to see unending lines of khaki-clad Americans walking on it.

After the pompous goose-step of the Germans, and Mussolini's almost as ear-jarring imitation called the Roman Step, the easy way the Fifth's two American divisions ambled through town received immediate attention and comment. "Look," surprised Romans exclaimed to one another, "at the Americans' undulating walk." The uninhibited gait Americans have picked up on the playing fields of Yale and Sleepy Hollow sometimes does something to their posterior that is strictly outside the European military tradition.

"How strange," Italians said, "but it is practical."

In odd, human little ways not always known to himself, Joe walked into the hearts of Romans as no conqueror could ever have done. But before he had an opportunity to alter his good first impression, we came--AMG.

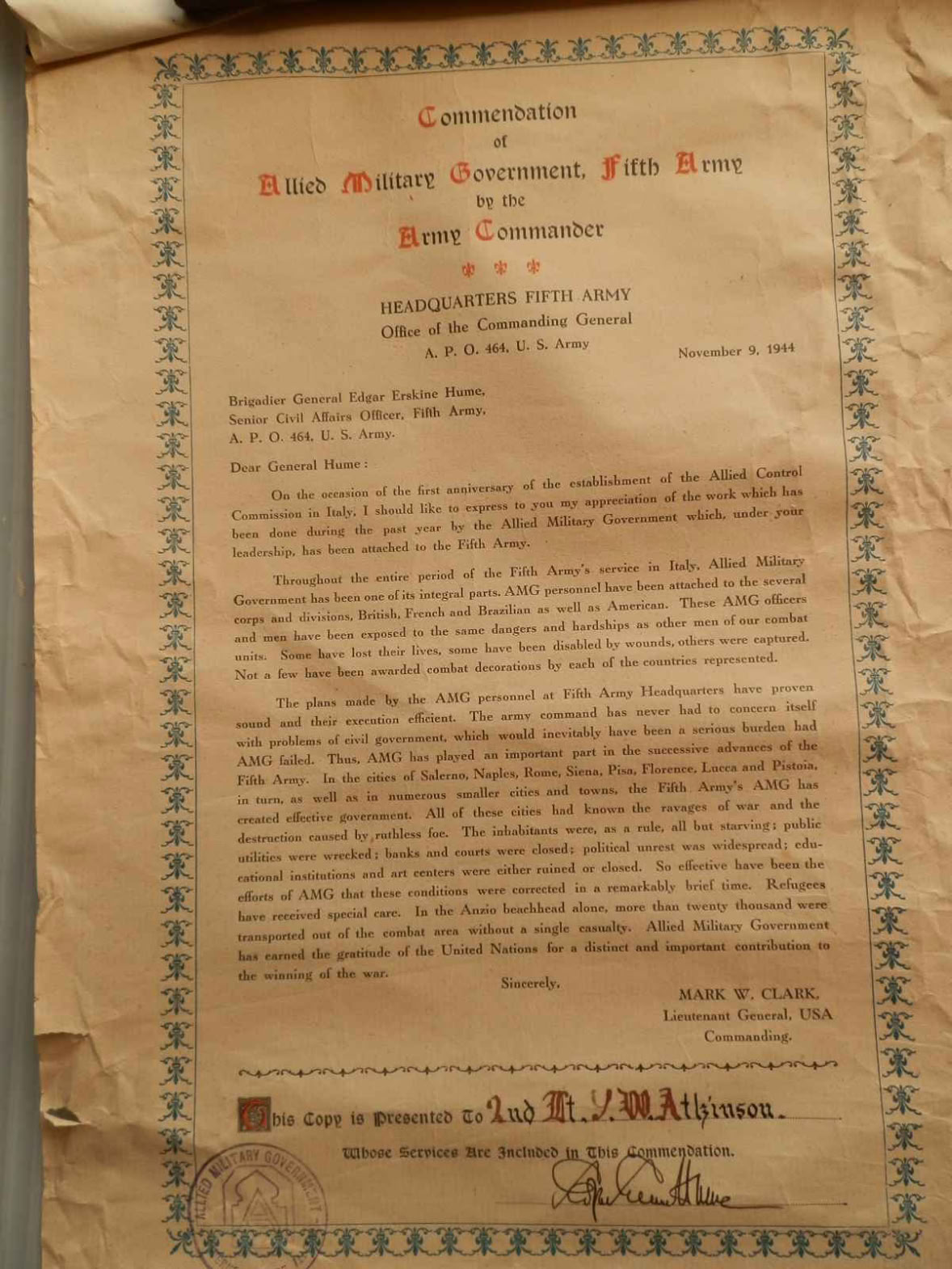

People in America and England had already heard something about us. We were a new experiment in allied military government, designed to carry out the work of liberation started by the two armies, one American and one British, in Italy. We were not all cast in the heroic mold of the almost legendary Major Joppolo, that Paul Bunyan of AMG achievement described by John Hersey in A Bell for Adano. Nor were there many of us in the original Allied Military Government Occupied Territory, or AMGOT an we were then popularly called, who were, as critics joyously alleged, Ancient Military Gentlemen On Tour. We were neither young Galahads, nor old men. Primarily, we were made up of average officers and enlisted men and now some of us, at the end of our first year of work and halfway up the Italian peninsula, were becoming uneasy at the signs of our gradually increasing failure.

Italians noticed it first. The little people in Italy's biggest city had awaited our arrival as they had awaited the coming of the troops, but with more apprehension among the strongly anti-fascist elements than might be expected at the approach of an allied military government representing two allied armies at war with fascists. It wasn't that AMG officers and enlisted men hadn't done anything for Italians. Too many times, particularly during the early days in Sicily, an officer alone, sometimes equipped with no more than a Jeep and a smattering of the language, but often neither, had entered ruined villages before the shooting was over and had started helping the wounded, burying the dead, and lessening in what ways he could all the known and the unimagined horrors brought by modern war to civilians. When he could, the British and American AMG-men who followed the famous British Eighth Army up the east coasts of first Sicily and then Italy, and the American Fifth Army across Sicily and from Salerno up the west coast of Italy, organized bomb and mine disposal squads and civil police forces, found water, established a local administration, gave it flour, gave it funds, cleaned up debris, organized transport,opened shops and schools, cared for war orphans and displaced persons, established hospitals, fought the black market, set up courts, tried cases, looked out for the hungry and homeless and generally attempted to be all things to all civilians within a radius of twenty and sometimes forty war-scarred miles.

Our knack for order helped Italy and sped victory, but it wasn't enough for those Italians who, while we were still separated by a battle line, had willingly risked their lives to listen to the glib promises of democracy coming from political warfare experts ensconced behind Psychological Warfare Branch microphones and radio transmitters in Allied occupied Italy. So far as politically conscious Italians could see, the military government of the Allies had no system for making democracy work. To be sure, the mayors we appointed we called "sindaci" and the hated fascist title "podesta" we abolished. But was not a sindaco, puzzled, middle-aged Italians wondered, a mayor chosen by the wishes of a majority of the townspeople? And, among the anti-fascists, doubt turned to suspicion when so many of our well-groomed, patronizing appointees turned out to be the very men in each village hierarchy the fascists had not made "podesta" only because they were not good administrators.

When, through our own or Italian initiative some of us began to choose mayors from among the less wealthy and more rugged membership of the local Committees of National Liberation, whose nationwide organization comprised the best anti-fascist leadership in Italy, these pioneers of modern Italian democracy were almost certain to meet with frowns and outright obstructionism from the allied military bureaucracy from which we all depended. This was particularly true of mayors who belonged to the Committees' most violently anti-fascist political parties, which supplied most of the partisans to Italy's fast growing and later Europe's most successful resistence movement. As for the partisans themselves, whose battalions later formed the vanguard of the allied advance through northern Italy, they were regarded officially as little more than brigands until they surrendered all their tommy guns, pistols, hand grenades and other arms to us--often under circumstances which made these heroic fighters for Italian democracy seem like criminals and left them deeply bitter.

Romans had heard, too, that with regard to the collection and distribution of wheat for bread, the staff of Italian life, affairs had gone badly. Down in Sicily, the great land owners had taken advantage of the breakdown in the fascist collection system and had refused to deliver their grain for milling. Soon hunger in the cities had forced us to commandeer trucks and go after it. But we didn't go as liberators. Instead, we raided the bare stone dwellings in desperate haste, gruffly ordered the uncomprehending peasants to sack and pile their master's grain onto waiting army trucks and then drove off before their bewildered gaze without so much as a "grazie" to relieve their abject serfdom. For twenty centuries prior to our arrival in Sicily, precisely the same thing had happened under seventeen successive foreign dominations. And when we took no pains to distinguish our operation from the former invasions, we, too, had to resort to the mutually exasperating road patrols, searches and criminal prosecutions.

Later, when we reached southern Italy, we attempted to popularize the compulsory fascist system of collecting grain by changing the name "Il Ammasso" (The Pile Up) to "Il Granai del Popolo" (The Peoples' Grainary). The Italians, seemingly knowing what to expect, never became very enthusiastic. Sure enough, well remembered faces began to reappear around the same collection depots and, just as the people expected, almost all the land continued to belong to the Sir Master--as it had belonged to the Sir Master's father and his father's father before him. So the people lost interest in Il Granai del Popolo. Meanwhile, the owners of most of the agricultural land in Sicily revived their own private police force to guard their huge estates. We approved the practice. Soon the lawlessness of Sicilians and southern Italians became a regular theme in our reports to headquarters, while outside our doors remarks began to be passed to the effect that for all our good sayings we resembled the fascist predecessors overmuch.

This not intentional badgering of the little people who farmed the land and fought fascism was at first accepted philosophically by Italy's democratic leaders as a by-product of war, which it partly was. Military necessity imposed certain logistic and practical tasks first; if existing fascist systems of meeting the problems of supply and distribution met the army's need at the moment we used them. And our latent desire to bring democracy was often thwarted by the handicaps of the very people we were trying to help. Probably the main blow most of us ever struck for Italian democracy happened when the always agitated roar element of the daily crowd of petitioners and litigants outside our windows, and its constantly elbowing main body in the adjacent rooms and hallways, pushed the unwashed bodies of its advance echelon onto our paper-littered desks.

On such occasions we might shout: "Why don't you Italians learn to govern yourselves?"

But It did no good. The words always stumped the villagers who could attach no meaning to them. "Yes, sir officer," the ranking official in the communal administration would always say, "I am at your orders."

But what military necessity and southern Italians not yet free from the bonds of their feudalism forced us to do was unnecessarily harsh and prolonged because of one thing we did not do. The great bundles of proclamations and general orders we pasted on the walls of every town and village we entered prescribed the limitations on civilian liberty necessary to achieve tactical security in the area; they gave Italians no instructions about self-government. And, for the most part, neither did we. Sometimes a conscience-stricken American officer would think back to his training days to see if he was overlooking some clue whereby he might bring more democracy to the people he was supposed to be liberating; but he found that besides a vague idea about the enemy regime he was replacing the main instruction about government received by AMG majors and colonels at the University of Charlottesville, Virginia, and the only knowledge of it revealed to AMG lieutenants and captains at Fort Custer, Michigan, had to do with the absolute sovereignty of commanding officers. Democracy, as a program of economic and political reorientation for people in occupied territories, had simply been left out of our Table of Organization.

None of us ever learned why. Being average Americans and, except for a sprinkling of mayors and one ex-governor, equipped with a completely authoritarian briefing about administration, it must have been expected that most of us would go about our job of establishing and maintaining order behind the lines somewhat as a benevolent gauleiter might do it, if a little less efficiently. Certainly, the American public hadn't known about this, nor had anti-fascist Italian leaders expected it; if it had been realized that we were sent to bring order without democracy there would have been much less surprise and bitter disappointment at the bigger events already beginning to happen on very much higher echelons of authority, events which punctured even the official hide of AMG in a good many places.

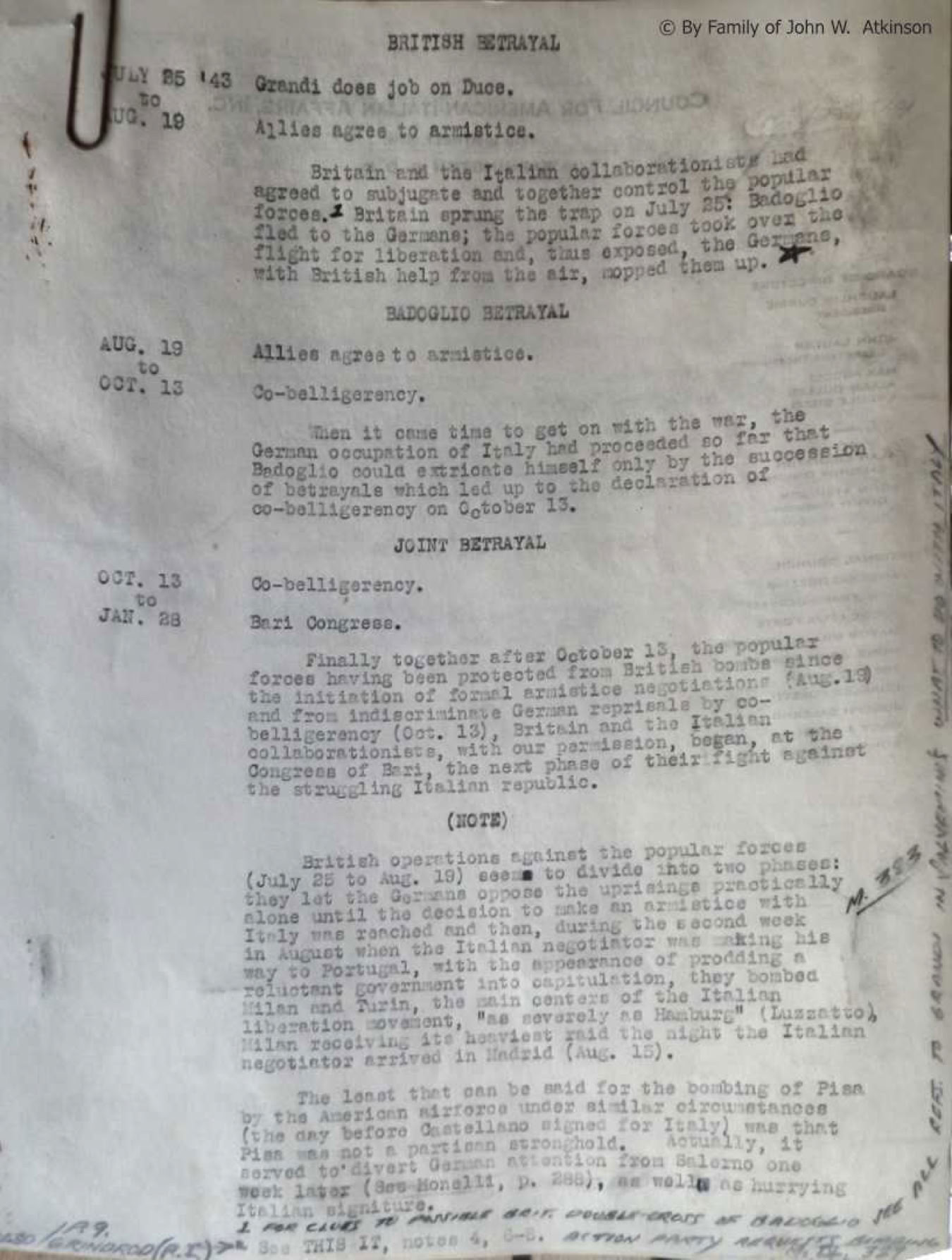

On July 25, 1943, while the Allies swept across Sicily toward the toe of the Italian peninsula, the Italian king and late Emperor of Ethiopia, Victor Emanuele III, acting on the advice of the Fascist Grand Council, had Mussolini arrested. He chose as his now prime minister, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, conqueror of Ethiopia and Duke of Addis Ababa, and carried on the war against the Allies.

On September 8, six weeks and many thousands of allied and Italian casualties later, General Eisenhower finally persuaded the stubborn little king and his reluctant marshal to abide by the terms of an armistice signed by their emissaries five days earlier, whereupon Victor Emanuele III and Badoglio immediately fled across Italy to the port of Pescara on the Adriatic. Boarding an Italian cruiser, they arrived at Taranto on the heel of the Italian boot about the same time the British Eighth Army's Fifth Corps landed there on the morning of September 9. During the night the American Fifth Army had assaulted the beaches a third of the way up the western side of the peninsula at Salerno and the next anybody heard the withered old king had his bandy legs thrust under the royal table at his luxurious villa in Possillipo outside of Naples and Pietro Badoglio, a member of the Fascist party, was making frequent visits aboard the British battleship Nelson riding at anchor in the harbor of Malta. His hosts were Harold Macmillan, Winston Churchill's good friend and British Resident Minister in the Mediterranean, and the U.S. State Department's Robert Murphy, architect of Oran.

A few weeks later, on October 14, the government of fascist Italy's Pietro Badoglio declared war on Germany, and collaboration was complete--even to the retention of General Mario Roatta as Italian Army Chief of Staff. Roatta was and still is wanted by the Yugoslav government to stand trial for war crimes and atrocities.

At first, Victor Emanuele III and Badoglio seemed remote and unimportant to Italians fighting Germans. But when the Allies finally authorized the Committee of National Liberation to hold its first congress at Bari the following January, Badoglio's "government of technicians" across the peninsula at Salerno was found to have a long arm.

"Owing to the danger of epidemics, I must ask for your health certificates," the Prefect of Bari told the partisans' delegates when they tried to enter his province.

When the delegates angrily brushed aside the prefect's protests, they found themselves confronted by General Roatta's troops and subjected to indiscriminate and unexplained arrests and detentions. When enough delegates did succeed in entering Bari anyway and proceeded to put Allied-occupied Italy's first congress on record as being unalterably opposed to the continuance of the monarchy, the Allies formally handed over administrative authority in southern Italy to the former Emperor of Ethiopia and to the Duke of Addis Ababa whom, just two years before, British troops in Africa had dispossessed with the usual blood, sweat and tears.

So, unpleasant memories of what their recent rulers had told them about pluto-democracies were mingled with Italian hopes for a better future, as we rode into Rome on the heels of the infantry on that bright June morning in 1944.

It was entirely owing to a tactical error that we started out by giving an impression of remoteness and unimportance. Following the established and heretofore practical occupational procedure of setting up administrative headquarters in the principal municipal building in a metropolitan area, our Rome planning group had assumed that the Campidoglio (Capital Building) would be just the place for us. Contrary to the eminent professors and historians on the planning staff who made this decision, however, the public life of Rome for the past twenty-two years had not centered upon the historic site on the Capitoline Hill that gave the word "capitol" to the world. It had been down at nearby Piazza Venezia, the great square in the heart of the city whose spaciousness afforded, so Mussolini thought when he stood on the balcony of his adjoining Palazzo Venezia, an auditorium sufficiently large for the eloquence of a dictator. And so, for the first day, our headquarters military government contingent of several hundred officers and men was left holding a seventy-five page top secret plan for governing Rome in comparative solitude. Meanwhile, beyond an adjoining museum, past a little church on the site of Juno's ancient temple, and on the other side of a huge monument to King Victor Emanuele II, thousands of curious Romans milled about Piazza Venezia in search of the missing military government of the Allies.

Our administration and prestige wasn't helped when the first arrival at our lonely headquarters on liberation morning turned out to be a septugenarian general from Badoglio's headquarters. "What...?" I started to ask the American nearest me when a procession containing apparently all of the sedans left in Rome by the retreating Germans drew up at the steps or the Campidoglio. But State Department Political Advisor Samuel Reber was already hastening to open the door of the first car to help its elderly occupant, General Roberto Bencivenga, up the steps to his office. With the Allied Control Commission's approval, Badoglio had appointed General Bencivenga civil and military commander of Rome for the interval between the departure of the enemy and the arrival of the allied troops. A young woman, apparently his secretary, held the carefully dressed old gentleman's other arm.

A little late, Bencivenga proceeded ambitiously about his duties, however, so that by sundown, posted on walls throughout the city alongside the proclamation of Fifth Army's Rome Area Commander, Major General Harry H. Johnson, which specified the obligations and duties of Roman citizens under the allied occupation, there appeared an equally impressive proclamation signed by General Bencivenga. With equal insistence it commanded Romans to observe a different set of rules and regulations. After stopping to peruse the conflicting announcements for a few moment, civilians usually uttered the expressive Roman "Beh?" as they lifted their hands in helpless little gestures and walked away.

Fortunately, it became our policy to remove Bencivenga from the Capitoline and his proclamations from Rome, but his presence during the next few days had the magic quality of making our cramped, musty offices fairly hum with activity.

Early the second morning another general, Angelo Cerica, Commander in Chief of the Royal Carbineers when the king and Badoglio fled Rome, but missing from his post since that date, strode into our hastily rigged AMG police office with the story that he had been living in the hills leading partisans. He requested that, as senior officer of the Italian civil and military police corps he would like his old job back. Actually, General Cerica's military government experience consisted of a tour of duty with his good friend and fascism's Rodolfo "The Desert Wolf" Graziani when, ten years before, the two of them had pacified the Senussi tribes of eastern Libya by dropping captured chieftains bound hand and foot from airplanes onto the market places of their rebellious villages. Now he counted on our demonstrated friendliness toward his king, and the fact that we relied almost exclusively upon the Royal Carbineers to help us restore and maintain order in the towns we liberated.

But the commanding officer of the two thousand eight hundred carbineers we had brought into the city the night before, tired, worn Italian Colonel Peronetti, drew me aside, pointed to the fat, shaven face above the pressed, beribboned uniform and growled scornfully: "That one has just come from the Vatican where he has been hiding all these months."

I moved across the room, and whispered this information to our AMG chief of public safety, former London Police Superintendent Lieutenant Colonel John R. Pollock. He immediately motioned the general off the chair he had set before him and escorted him to our commanding officer, American Brigadier General Edgar Erskine Hume. The fact that Angel Cerica actually had been cooling his heels on the Pope's one hundred and forty-four luxurious acres, while the Germans subjected his brave successors in office to prolonged torture and death and disbanded the carbineers, induced the decision that the General was unfit for a command in Rome. So with regrets suitable to one of his rank and distinction in the Badoglio regime, General Hume said no, we couldn't use him now, but...perhaps later...in the north.

Cerica, who had never once stopped smiling, smiled even more broadly and easily. It was not to be hard then; some Americans only talked collaboration with difficulty. It was the same way with the English. The Anglo-Americans didn't mean anything by it. Four months later, as he sat in comfortable headquarters in Florence in charge of disarming partisans in the Fifth Army's area of occupation, Cerica was sure that it was a thing that didn't make any difference.

A tall, gaunt, sun-burned Italian in a light brown uniform was standing in the middle of our office when we returned. "I am General Presti," he said, and paused. A black handled dagger in a black metal sheath attached to a shiny black belt, and polished black boots, completed the introduction. Presti represented the Italian Africa Police, the dread fascist colonial militia whose allegiance to fascism had never been compromised by "Italianism"-- an instinctive loyalty to Italian traditions and interests which in the end had made the carbineers unsuitable for Nazi police work in Rome.

"My troops wish to serve the Allies,," the fascist said haltingly. And then, as though realizing the enormity of his request, he implored, "Think of our wives and little children." His twelve hundred assorted desperadoes and cutthroats could well be proud of their versatile chief, for six hours later they were handing over their arms and uniforms in return for an allied pardon returning them to civilian life unhandicapped by their recent career against it.

Finally, through the crowd of collaborators and aristocrats pressing into our office seeking privilege, three Italian civilians with their hats in their hands made their way to the Colonel's desk. They said they represented the Rome Committee of National Liberation, and would the military governors like their advice on conditions in the city and their help on matters pertaining to the liberation? Also, would we please instruct our officers to stop arresting the Committee's partisans and taking their arms needed for the killing of fascists.

"Where did you get your over-night police authority?" AMG's Scotland Yard-trained Lieutenant Colonel Pollock demanded.

"From the Committee of National Liberation which fights fascism," one saids.

"Which we represent," another added.

"I am in charge here," Pollock replied authoritatively. "It is in the public interest that your police agents be stripped of their illegal authority at once. Tell your

partisans that. We mean business."

The Colonel spoke in excited English rising toward a shout, and the delegates needed no translation. It was just as clear as the negative shake of Badoglio's bald pate had been when, immediately after the fall of Mussolini, the Central Committee of National Liberation had risked coming into the open to ask the new premier of Italy to join the Allies and declare war on Germany. Tight-lipped, the three representatives of Rome's seventeen thousand active partisans, and the dead and the living dead who had fallen into German hands during the long, desperate, pain-filled underground fight turned and, looking at nothing in particular walked through the silent, curious crowd and out the door. I never saw them again.

Far up the shop-lined Via Nazionale, inside the Grand Hotel, ornate hostelry for visiting diplomats, British Lieutenant General Sir Noel Mason Macfarlane, D.C.B., D.S.O., M.C., Deputy President and Chief Commissioner of the Allied Control Commission for Italy, the Allied Control Commission's Executive Commissioner, Brigadier Maurice Stanley Lush, C.B.E., M.C., and its Deputy Executive Commissioner, Colonel Norman E. Fiske, A.U.S., were having a different kind of problem. It centered around the old difficulty of pretending to keep faith with the Committee of National Liberation whose partisans the Allies did not like but needed while collaborating with the enemies of a free Italy whom they did not need but wanted. The dilemma had its origin in the Allied Control Commission's fledgling days when, as head of the Allied Military Mission which negotiated the final armistice terms with the Badoglio government, General Macfarlane persuaded the king and Badoglio to leave their cruiser and return with him as the governing heads of Allied-occupied Italy--"the King's Italy" our British colleagues immediately began calling it. But the commander of the allied forces in Italy, General Sir Harold R.L.G. Alexander, whose American Fifth and British Eighth armies were now working up the western and eastern sides of the Italian peninsula, needed the continued support of the approximately two hundred thousand armed partisans on the German side of the fighting line. Allied leaders agreed therefore, that the base of the Italian government had to be broadened. The question before the Allied Control Commission meeting the delegates of the Committee of National Liberation in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Rome for the first time on June 8 was, how much of the collaborationist structure upon which the Allies were building the peace could be saved?

If State Department careerist Samuel Reber had followed less closely the opinions and actions of his counterpart in the British foreign office, and if the latter had not been so

determined to see and report only what he wanted to believe about Italian politics, both political advisors would have known that the people of Italy wanted a new world without fascism or fascists. As it was, they had to be told. After the allied advisors had gone through the motions of assuring the delegates that the Allies wore not trying to force Marshal Badoglio into their government, while at the same time clearly establishing the point that we did, however, favor his retention "under present conditions," the delegates' premier-elect, white-haired Ivanoe Bonomi, seventy-year-old ex-premier of one of the last pre-fascist Italian governments and chairman of the Rome Committee of National Liberation stood up.

"I have no place in my cabinet for anybody who has been compromised by fascism," he announced.

In a red plush chair provided by his allied friends, the ex-duke of Addis Ababa squirmed. It had not been pleasant for the septugenarian collaborationist who still wore the incriminating uniform of the Italian armies he had led into Ethiopia and Greece to answer the continuous chorus of inquiries coming from the civilian delegates who wanted to know what he was doing there. Now he rose, and, surrounded by aides and a cordon of allied officers, left the hotel.

With Badoglio finally off the agenda, the British foreign office spokesman reminded the delegates of their obligation as Italians to the Savoy monarchy. This time the usually preeminent glory and magnificence of British oratory was somewhat dimmed by Italian candor.

"We cannot consent to refashion a political virginity for Victor Emanuele," one delegate loudly announced, above a melee of accusations and supporting statements from his colleagues.

Wisely, King Victor Emanuele III's advisors had long foreseen the Committee's objections and twenty-four hours after the Allies entered Rome, after months of pleading, they finally had succeeded in persuading the mulish king to hand over at least the perogatives of his office to his son, middle-aged Prince Umberto, who became Lieutenant General of the Realm. Not so wisely, the interim successor to his father's dynasty, who had known no better than to accept a general's commission from Mussolini and to command the Italian troops that stabbed France in the back, appeared on the balcony of the Royal Quirinale Palace in Rome on the morning of June 9 and announced to a largely monarchist crowd of about five thousand that he had appointed Ivanoe Bonomi new premier of Italy.

Of course, a few already knew and more would learn that the Lieutenant General of the Realm lied. It was he who had been appointed, by his father with the consent of the Allies, and, instead of having called Ivanoe Bonomi and asked him to form a government, it had been the Italian liberation parties that had nominated Bonomi without consulting the Lieutenant General. Completely out of patience, an unidentified republican almost settled the monarchical issue for the time being by opening up with a small caliber pistol while Umberto was still on the balcony. The half dozen shots were wild.

London was appalled when word came that Pietro Badoglio, chief hope of the Italian monarchy, was now outside the government. Sunday afternoon, forty-eight hours later, Bonomi and his cabinet found themselves flying back to Salerno. Within another forty-eight hours General Macfarlane, who had permitted the new goverment to form without the fascist marshal, was in another plane speeding toward London. Thanks to their constituents--tens of thousands of armed and anti-fascist Italians--the trip of the Bonomi cabinet turned out best. After contemplating the panorama of Naples and its bay from an unfurnished villa on a hill near Salerno for nine days the Bonomi goverment didn't die--instead it kept Badoglio out, agreed to let Prince Umberto stay as Luogotenente of the Realm until an election could be held in a liberated Italy. On July 15, more than a month after we had occupied Rome, the new Italian government representing all six parties of the Committee of National Liberation was allowed to return to the capitol to administer Italian affairs under the direction of the Allied Control Commission.

When General Macfarlane arrived in London many of his friends in Rome were surprised to learn that "for some time," as the Allied Control Commission's director of public relations inadvertently revealed, "Mason Mac" had been suffering severely from a spinal complaint. So far as we who never saw him again know, his condition remained critical until the following year when as a result of the British national elections in June, 1945, he was elected to parliament by the Liberal Party. He never came back to Italy.

I WE CALLED IT LIBERATION

III

WHO KILLED DONATO CARRETTA

One day about three weeks before Cassino fell a young civilian stood at the juncture of a cobblestone alleyway called the Via Rasella and Four Fountains Avenue, which some extremely sentimental Italians who have been to New York say is the Fifth Avenue of Rome. Shortly, a platoon of German soldiers whose duties regularly took them down Four Fountains Avenue and through the Via Rasella made its scheduled appearance. When the soldiers, marching four abreast, reached a point about a hundred yards from where the young man stood, he slowly scratched the top of his head with one hand and sauntered off. As he did so another Italian dressed as a street cleaner standing beside a refuse cart about two hundred yards down the Via Rasella hastily blew on the tip of a half-burned cigarette, quickly held it against something inside the cart, and then disappeared. About two and a half minutes later as the platoon came abreast of the abandoned trash cart a terrific explosion shook the neighborhood; when German police arrived on the scene they found the torn and mangled bits and pieces of what had been thirty-two German soldiers strewn all over the little Roman backstreet for about fifty yards in each direction.

The German reprisal against the Italian underground was swift and awesome. Selecting two hundred seventy captive partisans and resistence workers from the German SS and Gestapo torture and interrogation chambers on Via Tasso, and taking fifty political prisoners held by Italian fascist authorities in the Regina Coeli prison, a German police squad transported the total of three hundred twenty Italians--ten hostages for each murdered German soldier--to the Ardeatine Caves near the ancient catacombs of Janarious, where they were taken inside singly or in small groups, shot in the back of the head with pistols, machine gunned and afterward the tunnels blown shut with mines.

Almost all of the prisoners delivered to the German execution squad from the ancient Roman prison situated on the north bank of the Tiber near the Vatican, which is called for no apparent reason "Queen of Heaven," were the personal choice of Pietro Caruso, a conscienceless Black Shirt militiaman whom Mussolini sent to Rome as chief of police early in 1944, partly to strengthen the fascist-republican war effort and partly to revenge himself on Romans because they had never mourned his absence; on the contrary, from the moment of his first fall from power on July 25, 1943, Romans had continued to live quietly and observe their usual unchanging habits, until increasing acts of violence such as the Via Rasella killings began to mark the Allies' slow advance toward Rome. The trial of Caruso, the first major fascist war criminal to be tried by Ivanoe Bonomi's newly constituted six-party coalition government, began on September 18, 1944. Five days later some thirty allied newspaper and cameramen witnessed Caruso die tied to a chair before an Italian firing squad in Rome's medieval Fort Bravetta, in much the same fashion as he had supervised the execution of Mussolini's son-in-law Galeazzo at Verona nine months earlier.

But on the first day of Caruso's trial the government's star witness, Donato Carretta, was lynched. Herbert Matthews, the New York Times correspondent who witnessed the former warden of Rome's Regina Coeli prison beaten senseless in front of the Palace of Justice, thrown into the Tiber and his lifeless body hung head downward from the bars of a first floor window in the Regina Coeli, wrote in his recent book "The Education of a Correspondent" that the cowardly atrocity so shocked and infuriated him that he swore that morning to write a story which would forever blacken the name of contemporary Romans and do the Italian government as much harm as possible. At least, the story was not a disappointment to Matthews. It not only almost burned through the paper on which it was printed, which is Matthew's own modest claim for it, but it unleashed a fury of indignation upon the head of the fledgling democracy already deep in the crisis into which the event plunged it.

Two smaller voices, one from each side of the Atlantic, approved the lynching. The day it occurred Randolfo Pacciardi, who led the Italian Garibaldi Legion against the fascists in Spain and now head of the Italian republican party, wrote in the editorial columns of his party's La Voce Repubblicano that some foreign newspapermen (meaning Matthews) did not understand that even Italians have blood and souls and expressed regret that their dispatches would cause further harm to Italy. Three days later, Lewis Mumford, in a letter to the editor of The New York Times rebuked Matthews for not understanding that what he had witnessed was punishment close to what the theologian calls the "Judgment of God."

Whatever their differences of opinion, it is symptomatic of the achievement of the Allied Control Commission in Italy that each of these moulders of world opinion agreed in one thing: they attributed the act of violence to the Italian people. But the people of Rome, where a lynching had not occurred in the past one hundred and fifty years, were not to blame for what happened to Donato Carretta.

"I pronounce you dead," Lieutenant Colonel Pollock had said with the impeccable efficiency of the London police superintendent as he got to his feet after briefly examining Carretta's body, still dripping blood and water on the stone floor behind the heavy portals of the prison where we dragged it after cutting it down from the window grating. As my former chief ordered an Italian jail official to certify in writing this fact he had just discovered, I looked at the lifeless face of the man who had been torn from my grasp in the rioting courtroom. First conscience and then reason told me that Donato Caretta's blood was on our hands.

Why had AMG's chief of public safety turned up at Italy's first war crimes trial almost an hour after it was scheduled to begin? The night before Lieutenant Colonel Pollock had been sufficiently aware of the possibility of violence to lock Caruso securely in a vault-like chamber beneath the courtroom where he was to be tried. Why had I, a lone lieutenant attached to the public relations branch of the Allied Control Commission, been the only allied official in the courtroom when the riot began? And the sixty-four dollar question--why had one of the most successful operators in the Italian resistence movement, a man who as prison director had daringly engineered the escape of over eighty political prisoners from Regina Coeli's dread sixth wing, been lynched when he came to testify against his hated former chief?

At first I blamed myself, and then slowly, because such things are hard enough to believe, much less discover, I learned who killed Donato Carretta. The separate events pieced together form a plot no one expects to occur outside of fiction; but when I learned how this brave Italian came to be murdered, and understood it well enough so that my knowledge of it could not be shaken by any instinct of decency or patriotism, I began to understand a great deal about war and peace, and especially liberation, in our time.

On August 11 Prime Minister Churchill had arrived unannounced in Rome and that same morning there had been a display of posters throughout the city charging that the days of the government of Premier Ivanoe Bonomi were numbered because it did not enjoy the confidence of the Allies. The sudden appearance of the prophetic posters on the morning of the British Prime Minister's precipitate arrival In the Italian capital, four weeks after the fall of Badoglio's government, had not been due entirely to coincidence. From the moment the delegates of the six national liberation parties forced the fascist marshal out of the government and the Allied Control Commission's Lieutenant General Sir Wool Mason Macfarlane was permanently recalled to London, Italy's former ruling classes, whose hope Badoglio was, had continued to receive open support and encouragement from conservative and British elements in the Allied Control Commission.

By working through such channels as His Excellency the Marchese Enrico Cittadini-Cesi, fascist foreign office careerist who was in Mussolini's Venice Palace office before the Allied Control Commission took him in as its chief of liaison with the new Italian government, the enemies of Italian democracy succeeded within the first month of the birth of the Bonomi government to bring about that chronic state of crisis which was to characterize its short, unhappy life. In the meanwhile, a comparatively small but highly articulate section of the press, led by the blatantly monarchist Italia Nuova, had been busy sowing defeatism and rebellion among Italians by blaming the government for chaotic economic conditions no post war Italian government could help and which, later events were to show, the Allied Control Commission deliberately prolonged.

The posters surprised no one, but it probably increased thoughtfulness in some quarters when it was demonstrated that Bonomi's government had no intention of giving up. All Badoglio got out of the long conference at the British Embassy to which both he and Bonomi were called by Winston Churchill (upon Churchill's return from Greece two weeks later) was a more bountiful lunch than was then generally available in Rome. As for turning over his government or sharing it with Marshal Pietro "I am the Duke of Addis Ababa" Badoglio, all the persuasive force of the British king's prime minister hadn't convinced Ivanoe Bonomi that this was the thing to do. Churchill himself now had Bonomi's word for it that even if the Allies did not, Italy did intend to break its ties with fascism.

The evening of the next day, August 25, an orderly and good natured crowd gathered on the Piazza Farnese in front of the French Embassy to celebrate the fall of Paris. When about five thousand persons were assembled on the square, one of them helped by others, had climbed to the balcony of a carbineer police station fronting on the piazza, torn down the Italian tri-color bearing the arms of the House of Savoy in the white, middle stripe and thrown it among the crowd. He had started to put up a red flag with the hammer and sickle when a carbineer rushed to the balcony, grabbed it from his hand and flung it after the monarchist flag. By the time the noise of the scuffling and the shouts and cries of a small group of agitators had attracted the attention of practically everyone on the square, Lieutenant Colonel Pollock and his deputy, also an AMG veteran from Sicily, big Major Percy Coxhead, calmed the disorder. While 250-pound Coxhead, unarmed, had quieted the hecklers, Pollock ordered that three flags--Savoy, Communist and French--be raised which, when done, seemed to satisfy everybody.

Besides being a good example of the competence of AMG's British police personnel, most of whom had been London policemen in civil life, and for whom, despite their occasional and possibly unwitting complicity in high-level decisions, I have great admiration and respect, the incident an the Piazza Farnese is important for two other reasons. First, the act of throwing the monarchist flag from the balcony evoked a great deal of cheering and other favorable comment from the crowd, thus illustrating the underlying cause of the public's widespread dislike and distrust of the carbineers, and serving as a warning, such as we had had before, that if ever a serious crisis in public order should occur Italy's oldest, biggest and best, but monarchist, police organization would be helpless. Second, the incident happened about the time Italy's twenty-fifth political party began to poke its queer-shaped head into the confused arena of Italian political life and, as Italians said of the predatory fascist party, began to "eat."

To Italians who early became aware of its existence, however, there was more to the frequent charges of graft and corruption laid to Unione Proletaria's door than met the eye. Apparently, in keeping with changed conditions, the dubious party met daily expenses by blackmailing wealthy fascists for "protection." But in the personality of its leader and his program seasoned observers of Italian political life sensed something strange and a little ominous.

Umberto Salvarezza, "professore" as he explained to the allied authorities who found him in the Regina Coeli soon after our arrival, was by his own account an ex-secretary of a former Liberian delegation to the League of Nations. Nevertheless, he was a tough looking character with a crossed left eye and a long prison record for blackmail, forgery and theft. In addition, as the investigating authorities could see when he took off his shoes, the Germans, as he alleged, for reasons that are not entirely clear, or somebody, had burned his feet. Shortly after his release from prison the resourceful professor, making himself out to be a patriot, began to be heard on both sides of the Roman political forum by publishing simultaneously "La Frusta," a newspaper so fascist in tone that he printed and distributed it clandestinely, and a so-called leftist paper, which he falsely alleged had been in circulation clandestinely before we arrived. The latter publication became the organ of his political party whose name appeared on the newspaper's masthead.

If Salvarezza's claim to the command of eleven partisan groups fighting under the banner of his political party in German-occupied Italy for an unspecified number of months is waived, the Party of Proletarian Union was born, at least so far as public knowledge of it is concerned, on September 8, 1944, when Professor Salvarezza held a press conference in a modest second floor front room on the Via Fornovo. On this occasion Salvarezza told representatives of the Italian press that his proletarian unionists were bent on uniting the forces of the proletariat "in a solid block beyond doctrinal disagreements and controversies on a common platform more economic than political, more practical than theoretical." The professor stated that his party did not care whether Italy remained a monarchy or became a republic; what mattered, he said, was that Italy get rid of the six parties making up the government as quickly as possible and establish, as he characterized it, "a Government composed of experts capable of operating for the welfare of the Country." Contrary to what one might be led to expect from a political party as far to the left as its name indicated, Salvarezza closed with a few words on Italian foreign policy in which he put the Party of Proletarian Union on record as favoring closer ties with Great Britain and the United States whose interest in Italian affairs, he said, would be a blessing for Italian recovery.

Politically, the event had no importance whatever, but Roman police and AMG public safety personnel remember the last week in August and the first week of September, 1944, as the beginning of a major crime wave which, in its way, exceeded anything that happened under the German occupation. Before the end of September the streets of Rome became unsafe for civilians at night, allied personnel began wearing side-arms for the first time since coming to the city, the American successor to the head of the Allied Control Commission, U.S. Naval Captain Ellery W. Stone, twice severely jolted the Bonomi government with urgent communications on the subject of law and order and, a short time before thousands of common criminals almost escaped from Regina Coeli when rioters set fire to its roof, there occurred the event I have set out to describe in this chapter.

Early on the morning of September 18 in a large villa on the outskirts of Rome an American officer in civilian clothes hurried through breakfast and hastily departed in the direction of the Palace of Justice. Rome headquarters of the U.S. Army's Office of Strategic Services had just received word through one of its Italian operators that Salvarezza's "mob" had been alerted. The agent had been unable to supply further details, but he knew that his American employers considered any information about Salvarezza important. Only a short time ago they had shown an interest that bordered on consternation when he informed them that their British counterpart, SO or Special Operations, by whom he was also employed, had Umberto Salvarezza in its pay.

I arrived at the Palace of Justice with two jeep loads of allied correspondents about 8:35 A.M. Looking back on it now I wonder if the OSS observer whose understanding of contemporary events had brought him there shared my own casual surprise at the fact that the front entrance was then almost deserted. However, Italy's highest court, a narrow, vaulted chamber in the middle of a courtyard formed by the ornate sides of the three story high Palace of Justice, was nearly filled with an all-Italian audience of several hundred persons, each an invited guest of the Italian government, including some families of Ardeatime massacre victims, witnesses and members of the Italian press.

We had been in the courtroom about a quarter of an hour and I was talking with Elvezio Bianchi whom Reynolds Packard sent to cover the story for United Press, when the restlessness and confusion which had seemed to be growing, from the moment the allied newspapermen entered caused me to look up and see Robert Hadfield of The London Times struggling to get through a crowd of persons now completely blocking the main aisle. I left Bianchi and started toward the door where several public security police assisted by civilians were trying to halt the entry of more people into the already crowded chamber.

I remember feeling as perplexed as the spectators looked who were beginning to rise from their seats and stare back at the confusion about the doorway. According to explicit instructions from the public relations branch of the Allied Control Commission that morning, I was to leave the courtroom before the trial began which, I saw by my wrist watch, was just about ten minutes off. No allied official shall be present, the directive had said: it was to be an Italian trial by the Italian High Court of Justice with no allied supervision of any kind. Despite the Allied Control Commission's three staff sections, four administrative sections, twenty-four sub-commisions, a half dozen departments, branches, divisions and committees, and a huge military personnel which permeated and managed every aspect of Italian economic, political and social life, it had been decided that on this morning the fiction of an Italian government was to be elaborately preserved.

That is, the authority that one would expect an allied control commission to exercise at the first war crimes trial to be held in Europe during World War II, was utterly lacking. As I started to push through the crowd now milling about me I noticed on a balcony above the main floor of the court a battery of allied army and civilian cameramen and photographers. Attracted by the disorder, they were already beginning to record the event of the morning for the eyes and ears of the world.

Once outside the door, whose massive wooden portals the despairing security police were now trying to hold shut by main force, the logic of events nullified, as far as I was concerned, the headquarter's order which had left this trial unprotected in the face of an oncoming riot. Along the intervening hallways and corridors leading from the main front entrance to the Palace of Justice, a turbulent crowd of Romans, led by agitators shouting death to Caruso, was converging upon the court. Rallying five carbineer privates and a carbineer corporal whom I found eddying about in the stream of persons going past us I helped them form a line at the foot of the narrow stairway leading to the courtroom.

"Let me in. Let me in," a coarse faced woman in a dirty black dress shouted waving a slip of paper in the air. "I have the permission."

More shouts and cries came up from the crowd and as newcomers constantly added their weight to those in front who now began to push against the carbineers, the Italian military policemen began to be forced slowly up the steps. In one of those crazy gestures that sometimes happen in emergencies, I reached past the straining police line and took the slip of paper from the charwoman whose voice had mounted to a piercing shriek. It was a forgery of the typed government pass I had distributed to the correspondents an hour ago.

"It is not good," I had just managed to say when one of the carbineers lost his footing on the top step, went down, and the crowd exploded against the courtroom door which the security police had meantime managed to lock from the inside. For a moment it held the shouting, struggling crowd. Then slowly the fastening and all at once the policemen on the other side gave way and a mass of people poured into the packed court.

When the vanguard of the crowd began to lose its initial momentum long enough for me to get my bearings I found myself about halfway down the center aisle rubbing shoulders with Rome Area Command's G-3, Lieutenant Colonel Howard Dodgen. During the five months the Fifth Army's Rome Area Command and the Allied Control Commission's AMG unit had planned together at Caserta for the occupation of Rome, we hadn't anticipated anything like this.

"Do you want a hundred M.P.'s," the Colonel shouted.

"Against orders, sir," I shouted back as I went on by him in the wake of a group of determined characters who seemed to be making for the anterooms behind the judge's bench, in one of which, unknown to me and never discovered by the rioters, Pietro Caruso and an accomplice, Roberto Occheto, sat sheet-white throughout the remainder of the morning. While groups began searching the rooms, and even the cellar where Caruso and Occhetto had spent the night, I entered the first room I came to, picked up a telephone and dialed Lieutenant Colonel Pollock's office in Colonel Charles Poletti's AMG headquarters, two blocks away from Fascism's sumptuous ex-Ministry of Corporations Building on the tree-lined Via Veneto where the Allied Control Commission sat.

"Alright, old boy," the Colonel said when I told him what was happening and repeated Lieutenant Colonel Dodgen's offer of American military police. "I'll be right over, but no M.P.s. Don't do anything until I get there."

As soon as I came back into the courtroom, Eduardo Longo, editor of PWB's Italian language newspaper Corriere di Roma, grabbed my arm and implored me for the love of God to do something. The excitement and pressure of the crowd pouring in through the still open front door had made people climb onto chairs and the tops of benches and tables. Fortunately, the raised platform on which the judge's bench was located put me in full view of everyone in the room when I climbed onto the desk and stood up.

II

ROME REVISITED

It seems there is a kind of providence in the lives of correspondents who return to enemy held capitals on liberation day. Invariably, it brings them into the arms and embraces of former underground friends before the smoke of battle has lifted. At this critical juncture (for I had been a correspondent in Italy before the war) I must ask the reader to face with me the fact that no such thing happened to me.

How could it? All foreign correspondents in Italy came under the watchful eyes of fascism's alert Ministry of Popular Culture and the so-called Voluntary Organization for the Repression of Anti-fascism, the dread OVRA secret police. We of the United Press did in particular after our bureau chief, Bud Ekins, telephoned a story to London describing Mussolini's stomach ulcers. After Bud had been escorted out of the country by two secret-service men, less than five weeks after his arrival in Italy, his successor, Reynolds Packard, quipped that Bud had established an all-time speed record for expulsion from Italy, never realizing that the OVRA's chief consultant on American baseball slang, in which Ekins had couched his message, was now his, Packard's, own highest paid Italian staffer. What we didn't know then didn't hurt us too much. But no conscientious underground worker who knew what he was doing made a practice of enlisting the moot aid of foreign journalists in the cause of anti-fascism if it involved revealing himself to us. We were constantly watched, our friends known. Contact with us by an anti-fascist brought him overwhelming risk of investigation, arrest, torture, death--and danger of arrest of not one, but many men and women of the underground.

The friends I found when I returned to Rome had never fought fascism.

"You can't go in there, lieutenant." It was an American sergeant who accosted me, as I approached the home of a dear Marchesa whose vivas for Mussolini and contempt for President Roosevelt in the easy-going days before the war had somehow never seemed subversive.

"Oh," I said, for the first time noticing the soldier's self-consciously furtive manner, the usual mark of the American attached to one of the secret societies of Uncle Sam's World War II army. "What's up?"

"Search me, lieutenant," said the sergeant who, it turned out, belonged to the U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence Corps. He rested the butt of his carbine on the ground. "I just can't lot anybody in, that's all I know."

I returned next day and apparently the crisis had passed. For I entered the familiar apartments by the front door. As I stood at the head of the short flight of steps that led into the spacious front room where my Marchesa sat with her faithful companion, Bianca, she eyed me coldly. Suddenly she recognized Me. "John!" she exclaimed. And then she commanded, "Get those wretches out of my house!" The Marchesa meant the United States Army counter-intelligence officers and agents billeted in some apartments she owned which were adjacent to her own living quarters.

"Quiet, dear. If you must, speak Italian," Bianca gently urged the Marchesa whose large, dark eyes, with more exasperation in them than I remembered, never left my face as I descended the steps and came across the room.

"Well," the Marchesa went on in English when I had embraced both women and sat down, "I do not suppose I need ask you what you have been doing."

"But Marchesa," I said, thinking to reassure her, "I am with the Allied Military Government. We do all we can."

"Poof!" she exclaimed, obviously as ignorant of what really was going on in Italy as she ever had been.

Gently stroking the Marchesa's hand Bianca said to me, "Gioia is still gone, you know." I hadn't known, but if I had thought much about the changing fortunes of fascism during the past year, I might have guessed as much.

"What can I do to help?" I immediately asked the Marchesa, who loved her absent niece as her own daughter.

"Who, you?" she said. "Try and get those American wretches out of my home."

The next morning at Counter-Intelligence Corps headquarters on the Via Sicilia I told an American major all I knew about the Marchesa and ended with my opinion that she was harmless for all her ranting. "I wouldn't worry, lieutenant," he said. "She'll get used to us. I guess she never told you how many of the Gestapo were living there before we arrived."

Gioia reacted differently than her aunt when a few nights later she returned to her home where I found her. This gifted young aristocrat had been my open-sesame to the circle of younger generation fascists which had revolved about Mussolini's daughter Edda Ciano and her unlucky husband, Galeazzo--ordered shot by his father-in-law a few weeks before U.S. troops landed at Anzio.

"Oh," she exclaimed. "How wonderful." Then I was embraced.

Gioia wanted to visit some friends she hadn't seen since her apparent abduction from Rome. "What beasts they were," Gioia told me as we drove across the city. "They took me with them, but I got away." Since she meant that her abductors had been those fascists who had grouped themselves around Mussolini when the Germans had whisked the dictator to northern Italy a few weeks after his arrest by the Badoglio government, and who now were fighting us under the banner of the Fascist Republic, I showed considerable interest.

"How did you get away from them?" I asked.

"Oh no you don't," Gioia laughed. "I'm saving that for my memoirs."

We arrived at one of those little apartments in the artists quarter on the Via Margutta, whose diminutive size and drab exterior always leaves you unprepared for the opulence and comfort inside. I had released Gioia to her joyous conferees and was reaching for a second pastry when I saw Colonel Norman Fiske, then the senior American Allied Control Commission officer in Rome, sitting at a nearby table looking at me.

"Would you care for some tea," an elegantly gowned Italian woman speaking English with a continental accent asked, beginning to pour the stuff out of a polished silver pitcher into a delicate porcelain cup.

"Thanks," I said, grasping the saucer too firmly and jiggling the half-full cup of tea as I brought it to me. The Colonel had seen me first and to my surprised nod of recognition he had returned only a cold, impersonal stare.

"Do you take sugar, or would you prefer a slice of lemon," I heard my hostess say.

"Oh, yes," I said. "Thank you." Did the Colonel remember me from before the war, I was thinking. He had been our military attache then, but this was the first time mutual Roman acquaintances had brought us together.

"Cookie?" The hostess was tentatively holding a plateful toward me and looking at me a bit strangely. I had ignored both the sugar and the lemon.

"Thank you," I smiled, picking up a spoon from the table. The hostess quickly put a cookie on my saucer and I slopped tea on it while crossing to the other side of the room where there was a group of young people about Gioia.

"I had a terrible time," a languid young man was saying, smoking a short stubby cigarette of German origin. "I just got back." Apparently everyone was speaking the precise English learned in continental European schools and in foreign capitals from English governesses. I remembered it well from before the war. It had a nice sound, but you could never be sure what you were going to hear.

A half hour later when Gioia was ready to leave, I had already had a long evening. No line of duty, this, I kept thinking. Or was it? I had chatted on friendly terms with Gioia's friends and, to use another expression inspired by the uniform of a British officer I spotted in an upstairs alcove, "carried on" as though that were the thing to do. Evidently it was. For six months later when the British Resident Minister in the Mediterranean came to Rome to take up his duties as Acting President of the Allied Control Commission, I became his military aide.

I felt better when a few nights later, I turned into a familiar tenement district near the Coliseum and ascended six flights of cold, stone steps to Nonna's flat. This had been my first home in Rome and "grandma's" wrinkled face was soon wet with tears as she held on to me and asked about Alan Cranston. Six years before, when I was a free-lance correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor and Alan an International News Service staff correspondent, we had shared this kindly old landlady's best front room and as much affection and care as she lavished upon any of her many children and grandchildren. But no sooner had I distributed my present for each wide-eyed child and protesting adult than I began to notice subtle changes. Where was the inevitable chicken that would be served with the spaghetti on the following Sunday, clucking and scratching and fattening on top of the garbage heaped behind the little wooden barricade directly under the kitchen sink? And what was Nonna's middle-aged son, Romeo, doing at home?

"The transport business," Romeo replied in answer to my question, "it went well at the beginning, but now the farmers are being returned to Italy from all East Africa." We were sitting about the large square table in the room next to the kitchen which by custom served as sitting room, dining room and one end of it, set off by a faded green screen, contained a bureau, a large crucifix and Nonna's bed.

I didn't say anything. I should have known better than to ask Romeo why he was back in his poor mother's home. Quietly, since military government in East Africa was a British affair, British military authorities were liberating Italy's colonies from Italian farmers and colonists. Of the approximately 200,000 Italian colonists in Africa, most of those returned thus far were still held in military encampments in southern Italy, under the supervision of what the Allied Control Commission called its Displaced Persons and Repatriation Sub-commission. A few of the refugees who had homes to go to were making their way north after the troops as best they could.

"Listen a bit, Giovanni," Romeo suddenly said, leaning toward me. "Can you get cigarettes easily?" The little boy who was the oldest nephew quickly looked at his uncle and then at me with bright, expectant eyes.

"No," I said slowly, looking at a spot on the table's unfinished wood surface. I was afraid this question was coming, or one like it. You had to eat somehow, and by the scrubbed appearance of the few dinner plates Nonna had been clearing away when I came in Romeo hadn't found out how yet. A teen-age girl whom I remembered as a child sat still at her place at the table and she was watching the spot too. I felt that Romeo was studying my face.

"It is not important," Romeo said finally. "I forgot that you don't smoke, I had an American cigarette just the other day and it seems the taste is still in my mouth. Mama!" He called to Nonna who had gone into the kitchen. "Bring the wine there in the cupboard and let us drink to Giovanni's return."

I went away after that. Outside, the swallows that had been diving, dipping and shrilly peeping over the rooftops at sunset were gone. I thought about them as I walked along the cobbled side-street in the moonlight. Were these the only part of the Rome I knew, the good as well as the bad, that wasn't changed so that now even the good seemed bad? Romeo was good, and so was his home and family watched over by his wonderfully good mother. Just the same, I never went back. The one thing better than not to help people you love, I had learned, is not to watch them suffer.

I transferred out of the AMG police unit with which I came to Rome and into the Public Relations Branch of the Allied Control Commission the last week in June, when criticisms of allied policies were beginning to mount in the Rome press. In their turn Romans, too, were beginning to wonder editorially why fascists weren't being purged, and why the poor seemed to be getting poorer, and hungrier. But when newspapers representing groups beginning to smart under the loss of privileges and emoluments they had always enjoyed under fascism began complaining of shortages of electricity and transportation, my new chief and the head of the allied Psychological Warfare Board got the same idea at the same time. I was given a PWB station wagon, a Jeep, drivers, rations for a week, eight Italian correspondents and instructions to cover the large section of Italy between Rome and Naples where the war struck hardest.

When the correspondents' vivid descriptions of towns where human life had been all but snuffed out by war began to appear in print, the few Romans who had missed luxury were quiet, and the many anxiously awaiting fulfillment of allied promises were awed by the realization of the price others, both allied and Italian, already had paid. During the whole period the eight gullible correspondents and I were negotiating this moratorium on the delivery of the Four Freedoms to Romans, there was only one important misunderstanding. "Radio Fascista," broadcasting nightly on a shortwave band from somewhere across the lines, kept alleging that the whole thing was a "nauseous Anglo-American propaganda play."

"Italians," I shouted holding up my arms. The sudden appearance of my uniform coupled with able seconding from Mario Berlinquer, the government prosecutor, and Italian newspapermen nearby, who shouted "silenzio" and "attenzione" while holding up their hands for silence, brought a magic calm to the room.

"Italians," I repeated, instinctively reverting to the days in Sicily when in similar fashion we used to protect ex-fascist grain manipulators in front of the People's Granaries, "you must maintain order in this court. Justice cannot be done with mobs."

As I continued to stand on the judge's desk, people quietly remained where they were and finally even the commotion about the front door subsided. For a moment the hysteria was gone, but not its cause.

"We want Caruso," a man shouted.

"Death to the fascist," another answered him.

Shouts and imprecations began to come from all parts of the room, but the mass of the crowd, once they had gathered their wits after the break-through into the courtroom, were slow to be provoked into new and useless turmoil. Meanwhile, at intervals of not more than ten seconds, the tight, little chamber was subjected to brilliant flashes of light as the photographers, apparently reluctant to let their subjects forget the dramatic event they were enacting, exploded one flashbulb after another.

Getting word that I was wanted in the judge's chamber, I got down from his desk and entered an anteroom where I found Lieutenant Colonel Pollock who had just come in through a rear exit. Also unarmed, and without an escort, he was listening to the presiding judge, Annibale Venturi, earnestly pleading that we adjourn and clear the court before it was ruined. In one corner of the room a large woman, in a black dress and wearing a wide brimmed black hat and dark glasses, stood quietly listening to all that was being said.

"Look out, sir lieutenant," an Italian whom I took for a court attendant whispered into my ear, "that one is a spy."

"Here, John," Pollock said, catching sight of me. "Go out there again and repeat what I tell you." My quickly mumbled words about the woman in black were lost in what appeared to be the Colonel's brisk handling of the situation.

"Roman citizens," I began this time, standing beside the judge's bench so I could hear what the Colonel wanted me to say in Italian. "The allies sympathize with your feelings toward Caruso and we will see that justice in done. Go tranquilly to your homes and an announcement will be made in the newspapers when the trial will be held."

I had finished speaking and the Colonel was beginning to gently urge the people nearest us to leave when a woman somewhere behind me suddenly cried out, "There he is!"

The next I remember a struggling mass of bodies began to move away from the witness bench and away from where we stood toward the center of the court. I reached the disputants and got one arm around the

head of a short, stocky man who was being slugged, kicked and beaten with chairs. Others protested he was not Caruso and they and one or two carbineers tried vainly to help him while all the time his attackers, who were in greater force, constantly kept taking him up the aisle toward the door. Then came shouts and cries from all parts of the room and the thing that had held most of the people quiet during the last quarter of an hour broke. In an instant the courtroom was a howling bedlam and somewhere into the mass of pushing, shoving, hysterical people the little man with the bloody face disappeared.

After some minutes during which I had difficulty staying on my feet, I saw that Pollock was accomplishing my general purpose by means of a short stick with which he was vigorously but harmlessly tapping and prodding people off tables and chairs and into some semblance of reason. It was a long process. And when the panic began to subside nobody in the still almost full courtroom wanted to leave.

"It is as we heard," sobbed the mothers and wives of Ardeatine Caves victims in the mourner's section, referring to a rumor started by the Fascist radio the night before. "The trial will not be held."

In the uproar created by the vortex of bodies which had swept the length of the courtroom and out the door in a matter of seconds the majority of the crowd including myself completely forgot about the little man who had been in the middle.

"Outside the courtroom, the crowd was monstrous," Zara Algardi takes up what happened next in his semi-official account prepared after an Italian commission of inquiry published its findings. "It wanted a victim," he states describing the mob emotion which now governed it, "and it would have one."

Instead of helping him escape up a stairway and into hiding in one of the upper chambers of the Palace, the Italian writer says of the policemen around Carretta when he suddenly appeared in the courtyard, they tried to take him through the crowd which immediately scattered them and hurled itself upon the bruised and trampled man. "No one could save him," Algardi continues, noting the futile efforts of one or two courageous carbineers. "Carretta had tried to defend himself; now he covered his face without a cry."

"Before this account goes any farther," Herbert Matthews states almost halfway through his understandably purple story which appeared in The New York Times the next day, "it will be best if I describe what I saw...I hung around the entrance of the palace, which faces the Umberto Bridge, and suddenly shouting was heard inside the court--that unmistakable, angry sound of mob fury.

"Inside, a few carbineers were trying, without force and without opposing the mob, to usher out a short, stocky man with thick lips, fuzzy hair and a face literally covered with blood. This was Carretta. Near the entrance, while his back was turned, a young man jumped on him with his feet, knocking him down, and others began kicking him. I asked a carbineer why he did not try to stop this.

"Someone grabbed a cane from an old man and began viciously beating Carretta over the head with the curved handle. The carbineers were standing around by the dozens, not more than a few yards from one another.

"Carretta tried desperately to get away from the blows and ran down to the end of the courtyard, where he was trapped. This went on for at least ten minutes, until the only Italian who showed any decency or courage--Lieutenant Borgomaneri of the Carbineers--asserted enough authority to get a few other police to help him rush the badly hurt but still conscious Fascist outside and into a car standing in front of the palace.

"He might have been saved then, but no one had the courage to drive the car away. The mob kept pressing around it, and men reached in to hit Carretta as well as they could. Lieutenant Borgomaneri then called on a dozen finance guards on horseback to clear the crowd away from the car. They timidly pushed their horses up amid the boos and whistles of the mob, but only one of them dared to draw his thin sword and hit a few men gently with the flat of it.

"However, the mob kept pushing in, and finally someone opened the car door. Carretta was dragged out, thrown on the ground, jumped on and kicked until unconscious. When I bitterly kept telling the crowd around me that this was worse than fascism and that Italy would get a black name throughout the world for this sort of thing, some shamefacedly admitted that it was bad."

Matthews next observes an American soldier at the wheel of a command car and British soldiers in a British truck refuse Lieutenant Bergomaneri's and another carbineer lieutenant's desperate pleas to take the senseless Carretta away in their vehicles. At this point there is an interval in the lynching which Matthews describes one way and Algardi another.

"For a while," Matthews states, "the crowd stood around the body on the street. One young girl with black hair and sunglasses, dressed well in a white summer outfit and looking like a student, had been one of the ring-leaders, and she

kept kicking Carretta."

"A group of assassins," Algardi wrote, "put Carretta on some car tracks in front of a streetcar held up by the crowd. Then they shouted for the conductor to go ahead." When he refused and the crowd began shouting that he was a fascist, the conductor, "with utmost calm," according to Algardi, "presented the ring-leaders with a membership card in the Italian Communist party."

Algardi, then notes that after failing to get the tram in motion by pushing, the crowd bore Carretta away once more. Here, in Algardi's account, occurred what Matthews next describes "the last horrid act of this terrible tragedy.

"Someone shouted: 'Throw him into the Tiber!' The limp body was dragged, not lifted, across the wide street to the beginning of the Umberto Bridge. Then it was lifted up and heaved into the water, some thirty feet below.

"The shock of the cold water apparently revived Carretta. As he was near the bank, he managed to crawl to the side and hang on, half in the water, just below the bridge. Some of the mob got a rowboat, went up to where he was and pushed him back into the water. Whenever he tried to struggle to the bank they hit him with their oars and pushed him back."